Unaltered photo by Debbyrnephotos via Wikimedia Commons, Attribution 2.0.

A downloadable version of this lesson is available here:

The language we use to communicate—along with other cultural artifacts such as images, films, music, and social media—has a life well beyond simple denotation, or surface meaning. Language is infused with normative cultural values, hegemonic power structures, bias, and subjectivity. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) describes a series of approaches to how socio-environmental (S-E) researchers may critically analyze texts and cultural artifacts to reveal these connotations and draw out the larger narratives that they support. What is the social context of the story being told, and why is the teller relating it in this particular narrative structure, lexicon, and moment in time? The goal of CDA is to reveal submerged power structures and elaborate on the role of discourse in both reflecting and constructing social realities. Burke et al. (2015) investigate how environmental journalism affects public knowledge and the collective desire to act toward conservation. They conduct an analysis of a regional newspaper in Appalachia to explore how the journalists discursively construct the natural environment and its interrelation with human activities and how they write about their favored forms of environmental governance.

In this lesson, instructors will select an online periodical that reports on local environmental news and natural history, or they may choose a national outlet like The New York Times, The Washington Post, or a journal like National Geographic, Orion, High Country News, Garden & Gun, or Sunset Magazine. Instructors will lead learners through a narrative and keyword analysis of environmental reporting in order to analyze the social messaging of environmental ideas, the types of narratives used, and tonal elements like human enjoyment of natural amenities versus human causes of environmental degradation. These discursive elements will help learners recognize editorial choices, bias, connotation and subtext and enable them to grow more aware of the complex ways that language constructs environmental realities, and thereby influences public opinion and policy.

- Explore how local and national journalism presents particular S-E issues, learn how to separate denotation from connotation, and identify cultural bias and hegemony in writing.

- Seek to locate erasures or subordinations through the lack of discourse on a subject.

- Translate popular discourse into themes and reveal patterns of narrative and meaning-making that support particular views of the governance of S-E systems.

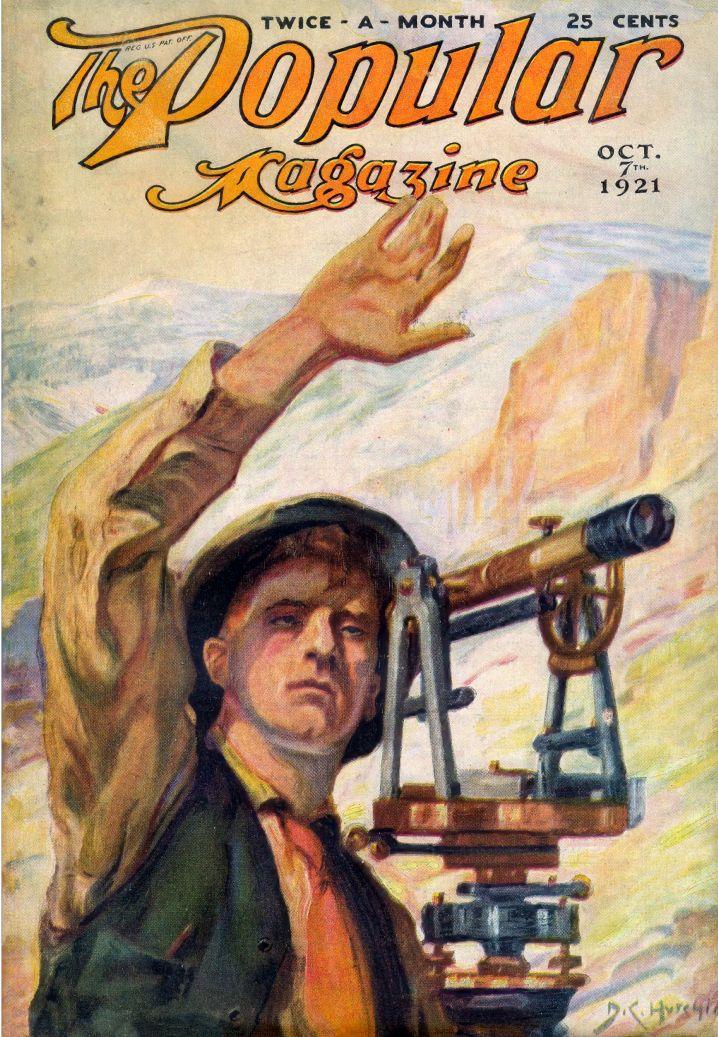

For 5 minutes, discuss the visual discourse in this cover image from a 1921 magazine. Ask interpretive questions, such as:

- What are the environmental context, cultural values, and effects depicted in this image of the surveyor at work?

- Does the image display normative or hegemonic American values and identities?

- What does the image denote, and what does it connote? Suggest some connotative keywords or themes (e.g., conquering wilderness, progress, development).

- More than 100 years later, how may we experience its visual rhetoric differently from how its original audience might have perceived it?

- In a contemporary version of this image, what elements might be depicted differently?

Critical Discourse Analysis: Environmental Journalism (Two, 75-minute classes)

-

As preparation for these sessions, the instructor should decide whether they wish to analyze a column in a local newspaper or campus publication or to analyze a regional or national one from the suggestions listed in #4 below. The instructor will need to provide access to online columns that are searchable as PDF or HTML files (Ctrl-F search function). These articles may be behind paywalls, but they are often accessible through university libraries’ online portals. Learners may use paper copies, but the instructor should consider how this format limits learners’ ability to quickly search for keywords and analyze themes.

-

Learners should prepare for the session by reading the SESYNC Explainers Overview of CDA, Narrative Discourse Analysis, and Qualitative Content Analysis and the paper by Burke et al. (2015), paying special attention to the highlighted portions. Learners should bring their own laptop for this session.

-

(10 min.) In class, after The Hook above, review the lesson PPT slides on the basics of CDA.

Document -

(5 min.) Divide learners into small groups of ~four individuals. Instructors may opt to have learners vote on which target publication they will analyze, or instructors may choose beforehand. Instructors may also choose to specialize in one approach and have many readers for each piece (i.e., choose only one of the following three options for all groups) or generalize the analysis and provide slim coverage of a variety of articles (i.e., choose all three and delegate single groups accordingly).

The options include:

A local or campus publication that at least occasionally includes articles on natural history, enjoyment of the local environment, and/or discourse on activism and governance of natural resources. This option is the closest to the Burke et al. paper.

A comparative analysis of the discourse in environmental columns of national newspapers:

- Margaret Renkl’s weekly Opinion column in The New York Times versus Harry Steven’s Climate Lab column in The Washington Post

A comparative analysis of the discourse in journals with contrasting editorial aims, geographies, and audiences. Learners might select a comparative theme, such as climate change, land use pressures, or the enjoyment of the natural environment. For example:

- High Country News versus Orion Magazine

- Garden & Gun versus Sunset Magazine

-

(25 min.) Once the groups have chosen from the above options, groups will screen and download relevant articles, aiming for each group to review 4-6 (each learner will review 1-2 at this stage). If this is a comparative analysis between publications, make sure there is equal distribution of articles from the two sources. The quick readings should give learners a sense of the topics, rhetorical approach, and major themes based on keywords that the authors use. Then groups should discuss their own terms of analysis by asking and discussing within the group:

What keywords are essential to establishing the tone and topical focus across pieces? Identify at least five keywords and variations or synonyms that groups should search for.

- Articles on the local environment have tonal variations, seen through keywords such as “beauty” and “harmony” versus “fragmentation,” “degradation,” or “restoration.”

- Publications may show a topical bias toward domesticated nature, like “gardens” and “arboretums,” or wild nature, like “wilderness,” “preserves,” and “rangeland.”

- Authors may integrate “humans/people” into their pieces or pointedly exclude them.

What ethical stance does the author imply in the article’s depiction of human activity and change in ecosystems?

What is the distribution of rhetorical tactics among ethos (author’s reputation), pathos (emotion), and logos (facts and statistics)?

-

(30 min.) Groups now use these analytical tools—keywords, topics, and rhetorical approaches—to conduct a CDA. Each of the four group members should closely re-read each article (5-7 min. for each). Note keyword-use quantities (Ctrl-F to search); their effects on tone and topic; issues of agency, ethics, and regulation; and the rhetorical tactics employed. Share findings within the group and delegate tasks for preparing a short presentation.

-

As homework, have groups analyze and prepare their findings for a short (10 min.) presentation in the next class. The presentation should include a quantitative keyword analysis, qualitative tonal and rhetorical insights, and a comparative view across publications or across a given time span.

-

(10 min.) In the next class session, groups may briefly review their data and finalize their findings.

-

(50 min.) Give each group ~10 minutes to present their findings and quickly answer questions.

-

(15 min.) With the remaining time, conclude with the full group’s observations on how various journals use discourse to depict environmental issues. The discussion might include:

Differences in editorial tone and content, and theories for why a publication follows this ethos based on geography, readership, cultural mores, and/or political views.

Hypotheses on how the tone and content of articles affect the readership’s sense of the human role in environmental change (both + and -). How does the discourse construct narratives about environmental governance, individual agency, erased or marginalized stakeholders, and culture-driven impacts on S-E systems?

-

(Optional Extension) Learners may find it rewarding to conduct a deeper discourse analysis by reviewing more articles or taking an alternative approach to the one chosen in #4 above. If the discourse analysis has reviewed a local newspaper, learners might write letters to the editor about what they found and how the paper might better serve the interests of its readers.

-

Critical Discourse Analysis

This 12-page chapter within the larger handbook describes CDA in depth and applies the work to educational and institutional settings and real-life problems. The chapter is a useful primer to exploring more specific settings and insights of other kinds of discourse analaysis.

Fairclough, N. (2012). Critical Discourse Analysis. In M. Handford, & J.P. Gee (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis (pp. 9–20). Routledge.https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203809068

-

Ecolinguistics: Language, ecology, and the stories we live by

This short monograph provides a framework for understanding and applying ecolinguistics to diverse topics including consumerism, lifestyle rhetoric, poems, images, newspapers, and films. It includes chapters on ideology, framing, metaphor, identity, and erasure.

Stibbe, A. (2020). Ecolinguistics: Language, Ecology and the Stories We Live By (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367855512/

-

Theoretical framework for ecological discourse analysis: A summary of New Developments of Ecological Discourse Analysis

This open access article provides an ecological grammar for understanding several constructs of ecological discourse. As a summary of a book, it’s an accessible length for a quick comprehension of how environmental representation can frame discourses of eco-benefit, eco-ambivalence, and eco-destruction. It provides many flow diagrams that go into the linguistic tools for analyzing language construction.

Cheng, M. (2022). Theoretical framework for ecological discourse analysis: A summary of New Developments of Ecological Discourse Analysis, 8(1), 188-226.https://doi.org/10.1515/jwl-2021-0030