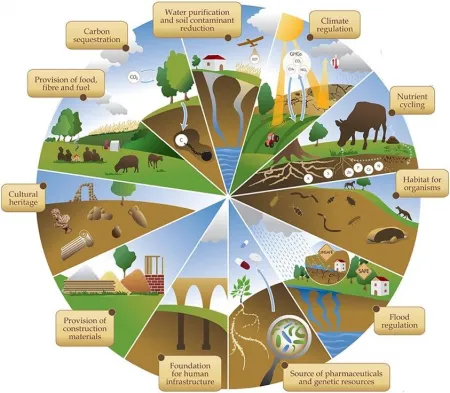

Figure 2 from “Soil ‘Ecosystem’ Services and Natural Capital: Critical Appraisal of Research on Uncertain Ground”

by Baveye et al. (2016). https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2016.00041

Diagram courtesy of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

To view in your browser and/or download the lesson, click on the PDF below:

Forest remnants persist in cities despite the intensive land use transformations of the last century. Some small forests are old-growth areas set aside as intentional preserves, some are remnant spaces seen as difficult for development because of riparian or topographical concerns, and others are secondary forest communities that grew in successive stages after farmlands or industrial centers fell into disuse. Whatever the history of these forest patches, they represent a major resource of natural capital that humans will continue to manage and develop as we become increasingly urban dwellers in the 21st century.

The first lesson on Urban Forest Patches (UFPs) delved into the potential ecological significance of novel socio-ecological ecosystems, which support a unique community including native and non-native species and display historical impacts of both human use and ecological succession. In a field trip to an UFP, learners detailed the factors that challenge the resilience of small forest patches and looked for value and potential of UFPs that may be unnecessarily derided as weedy, trashy, or dangerous.

This second lesson will explore the socio-environmental dynamics of UFPs by immersing participants in a role playing experience, where they will simulate being ecosystem managers tasked with working together to select management strategies that produce the greatest net benefits relative to particular ecosystem services, while maintaining the resilience of the ecosystem as a whole. Groups of learners will evaluate specific ecosystem services in a UFP and argue for a particular management regime to enhance those services. They will also have to factor in other complementary or competitive management strategies directed toward other ecosystem services. This exercise will elucidate how management of many ecosystems in UFPs involves tradeoffs, and how ecosystem managers must negotiate to plan for the most positive overall outcomes across socio-environmental services.

- Synthesize ecological with aesthetic, psychological, and practical elements of UFP governance.

- Consider several types of ecosystem services that may emerge from UFPs, making them functional and valued socio-environmental systems.

- Diagram eight types of ecosystem services and develop management regimes that maximize potential community benefits while acknowledging tradeoffs.

- Take an integrated approach to conservation, restoration, and intervention ecology to make effective governance decisions rooted in the current reality of rapid ecosystem change.

Have learners individually recall a forest ecosystem that they value. Learners may choose any forest that is familiar to them. Ask them to mentally embed themselves in the forest for 2-3 minutes. What sensual impressions can they summon: sights, sounds, scents, textures, and tastes? Have them write these recollections down as they come to mind, and ask them to review these sensual impressions with perception rather than judgment. For the last few minutes, ask learners to “translate” a sensual impression into an ecosystem service. For example, if they recall an auditory environment of birdsong, have them translate that into “wildlife habitat.” If they recall sour smells from a creek, have them translate that sense into “water quality.” They might even recall an emotion caused by sensual impressions, such as “calm” or “fear.” These can translate into ecosystem services or disservices related to “aesthetics” or “education.” Ask learners to share these sense-to-service equivalences and write them on the board.

Socio-Environmental Services of UFPs (one, 75-minute class)

Prior to the session, have the participants read the following article, paying particular attention to the highlighted areas, the section “Social Dimensions,” and Figures 1 and 2. Managing the Whole Ecosystem: Historical, Hybrid, and Novel Ecosystems by:

-

(10 min.) Start by reviewing some of the socio-ecological elements of UFPs using the PowerPoint below.

DocumentUFP Lesson 2 PPT.pptx (2.52 MB) -

(10 min.) Review insights from the previous UFP Lesson 1 about community composition, ecosystem services, and UFP burdens like edge effects and invasive species. Instructors will use the UFP from the class field trip in Lesson 1, or, if this is a stand-alone lesson, provide an overview of a UFP near your campus. This overview should involve the patch’s location, history, present species composition, and its uses or disuses. Ideally, you should provide learners with a website or another research tool to find out more information. In a pinch, instructors can use the websites Friends of Guilford Woods and Save Guilford Woods, which have information on native and invasive species, hydrology, and governance disputes in an urban forest patch in College Park, MD.

-

(5 min.) Carefully review Figure 1 in the Hobbs paper below. Assess how these researchers use rose diagrams to plot out: a) characteristics and management approaches versus b) different combinations and provision levels of ecosystem services (ES).

DocumentHobbs.Figure 1.pptx (114.77 KB) -

(5 min.) Assign participants to the following eight ecosystem service groups that are provided by urban forest patches (part [b] of the Hobbs Figure 1 is the analytical model):

Food/Fiber Production

Human Shelter

Water Quality/Quantity

Carbon Sequestration

Local Climate Regulation

Biodiversity Maintenance

Recreation/Education

Aesthetics

-

(15 min.) Introduce methods of analysis for estimating specific ES in a rose diagram. Ask groups to evaluate their ES on a zero-to-three scale as it relates to the UFP selected in Lesson 1 (or the Guilford Woods example provided in that lesson). Let the participants know that such evaluations are not static; they may be enhanced by management choices that direct the UFP into an improved condition. Additionally, if groups are uncertain about what value to assign, the whole class might have a brief discussion and come to a consensus. The instructor may also provide ranges, for example: a “one” could indicate 1-33% of potential service; “two” could indicate 33-66%; and, “three” could indicate a service provided above 66% of the UFP’s potential. As such,

“Zero” indicates that the ES is not present in the UFP.

“One” indicates that the ES is minimal in the UFP.

“Two” indicates that the ES is moderately provided in the UFP.

“Three” indicates that the ES is highly functional in the UFP.

Note to instructor: If the participants are using the Guilford Woods UFP, for example, an appropriate score for food/fiber production might be a “one” because the novel ecosystem has a few PawPaw and Persimmon trees that provide minimal food for humans.

-

(10 min.) Bring all the participants back together and on a board or in a software program, compile a rose diagram for the UFP with each of the eight dimensions of ES indicated on the zero-to-three scale. Exhibit this diagram for all learners to see.

-

(10 min.) Now ask each group to form a management strategy that would enhance their ES beyond its current state. For example, if their ES is “carbon sequestration,” what management initiatives would support greater provision of this service? Seedling planting, minimal soil disturbance, and allowing dead wood to stand or remain as fallen logs in the forest would all contribute to enhancing this ES.

-

(10 min.) Now groups must integrate ES goals by considering how their single ES-directed management plan might affect other ES in this forest. Using the previous example, while carbon sequestration may improve by leaving dead wood, other ES, like “aesthetics” and “fiber production,” could be diminished. On the other hand, complementary ES, like “biodiversity maintenance” and “education,” could be enhanced by leaving dead wood. Ask each group to sketch out a management regime that maximizes multiple ES provisions while acknowledging the detriments that may come to other ES from this management pathway.

-

As homework, have a representative from each group post their ES-directed management strategy, including the complementary and competing outcomes for other ES provisions (they should address the seven other ES as either complements or competition).

Ask all learners to “reply” to at least two management approaches from other groups to spur discussion. Ask them to propose different viewpoints in service to the goal of the greatest provisioning of ecosystem services and resilience of the system. For example, if the food/fiber production group posts that carbon sequestration and local climate regulation are complementary ecosystems services and biodiversity maintenance and recreation are competing outcomes, another participant might reply that food production in polycultures may actually support biodiversity. They might also suggest that food plots are seen as places of recreation and pleasure by many who participate in urban food movements. The point of these learner replies is to further synthesize complementary ES outcomes without misrepresenting the competing interests among some ES.

-

Urban Forests as Social-Ecological Systems

This chapter provides useful information on why urban forest patches are examples of socio-environmental systems that can provide valued ecosystem services, but also disservices and costs due to maintenance to survive.

Vogt, Jess. (2020). Urban Forests as Social-Ecological Systems. In: M.I. Goldstein & D.A. DellaSalla (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the World's Biomes. (pp. 58–70). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.12405-4

-

Human and biophysical legacies shape contemporary urban forests: A literature synthesis

This synthesis article discusses some of the major human and biophysical drivers throughout history and their associated legacy effects as expressed in present urban forest patterns. The authors argue that to understand urban forests and the mechanisms that have defined their character, a historical perspective is essential and researchers should use both qualitative and quantitative methods to help imagine potential futures for these and other urban forests.

Roman, L.A., Pearsall, H., & Eisenman, et al. (2018). Human and biophysical legacies shape contemporary urban forests: A literature synthesis. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 31, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.03.004

-

Nature is everywhere—we just need to learn to see it

Environmental writer Emma Marris reflects on the importance of recognizing that nature is all around us. She argues we don’t need to go to special preserves to enjoy the benefits of nature—just go outside your door. She stresses we should not define nature as that which is untouched; instead, novel ecosystems are all around us and may become the norm. She believes we should embrace that.

Marris, E., (2016, June). Nature is everywhere—we just need to learn to see it. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/emma_marris_nature_is_everywhere_we_just_need_to_learn_to_see_it?language=en

-

“Novel Ecosystems” are a Trojan Horse for Conservation

This opinion article focuses on the debate between proponents of the novel ecosystem concept and those who argue it is both scientifically flawed and misdirected. Simberloff and colleagues outline those flaws as well as the negative conservation and restoration implications of adopting a novel ecosystem perspective.

Simberloff, D., Murcia, C., & Aronson, J. (2015, January 21). Opinion: “Novel Ecosystems” are a Trojan Horse for Conservation. Ensia. https://ensia.com/voices/novel-ecosystems-are-a-trojan-horse-for-conservation/