Twent-four percent of all food produced in the world is traded across international boundaries. Increasingly interconnected food networks shuffle soybeans from Brazil to China; fish from China to the United States; and corn from the U.S. to Japan.

As countries become increasingly dependent on an increasingly globalized food trade, local pressures can give way to socio-economic and socio-environmental impacts felt around the globe. Changes in policy or extreme environmental conditions in one country can affect the food security of another thousands of miles away.

But just how vulnerable are we?

New research published this week in the online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences indicates how the relationship between global population and food supply is becoming more and more sensitive to demographic and environmental fluctuations. At particular risk are nations where land and water resources are scarce and, as a result, food security—typically defined as sufficient access to safe and nutritious food that meets the dietary needs of a population—is reliant on imports. Such interdependence could lead to instabilities with possible catastrophic consequences: escalated food prices, increased poverty and hunger, social unrest.

“We’re in a new era in that global trade gives us access to food produced halfway around the world, which we can import to help cope with shocks to local agricultural systems. But at the same time, international trade networks expose us to the local shocks of other regions that can propagate into global crises,” said Paolo D’Odorico, sabbatical fellow at the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) and one of the study’s authors.

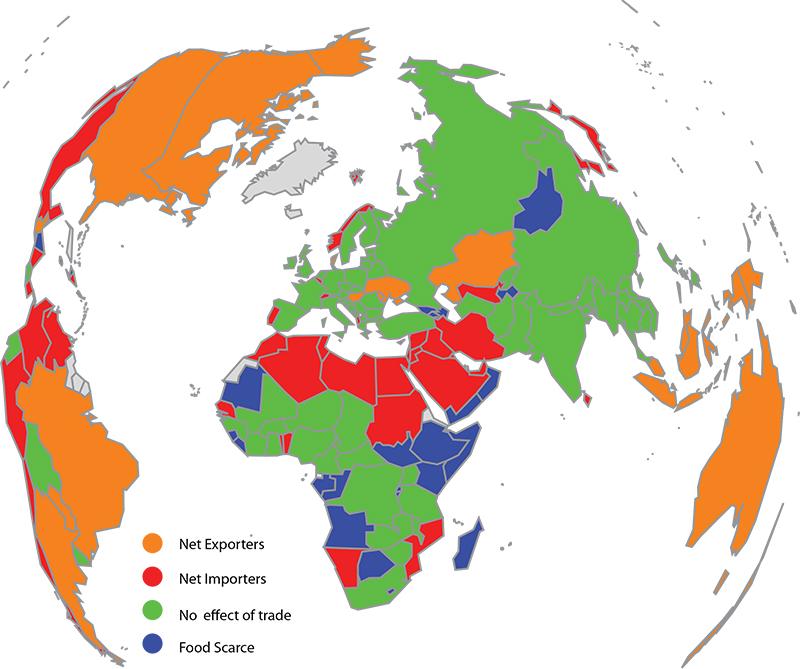

The study—co-authored by members of a SESYNC synthesis group—evaluates the food security of more than 140 nations with populations greater than one million. The researchers say their findings indicate how, through international trade and fluctuations in supply-and-demand, the global food system is losing resilience and becoming increasingly susceptible to crises. Using global population, food production, and trade data in conjunction with complex network analysis, they mapped hotspots of food insecurity.

“This is the first time someone has attempted to mathematically quantify the level of resilience of the global food system—specifically, how likely a country’s food supply is to absorb or recover from shocks,” said Samir Suweis, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Padova and lead author of the study.

The authors categorized each country into one of four groups:

[A] Exporting countries in which population growth is driven by domestic resources—including the U.S., Canada, Australia, and Argentina.

[B] Trade-dependent countries that cannot sustain their population without importing food—including Japan, Jordan, Egypt, and Algeria.

[C] Countries in which trade does not substantially alter food availability or population growth (or vice versa)—including China, Bangladesh, Ecuador, and Germany.

[D] Countries that are in a state of chronic food stress because their populations have grown above levels that could be sustained from both domestic production and trade—including Somalia, Angola, Ethiopia, and Senegal.

The results show that countries in groups B and C are most sensitive to perturbations throughout the food trade network and, therefore, are at the greatest risk of food insecurity. It’s a finding the researchers found surprising: countries in group C, which do trade but are not dependent on imports, are highly vulnerable because of the interconnectedness of the trade system.

D’Odorico and Suweis say that more research is needed to understand these results.

“A possible explanation might be that these countries are presently self-sufficient—but just barely so. They may not have access to sufficient reserve resources to cope with demographic shocks, exposing them to greater potential risk," D’Odorico said.

The study can be accessed online at: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/short/1507366112

The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, funded through an award to the University of Maryland from the National Science Foundation, is a research center dedicated to accelerating scientific discovery at the interface of human and ecological systems. Visit us online at www.sesync.org and follow us on Twitter @SESYNC.