Hummingbirds may be some of the lightest birds on Earth, but in the history of central Mexico’s indigenous peoples, they hold significant weight. Viewed as a warrior deity, Huitzilopochtli, an important Aztec god, was often depicted as a hummingbird among the Mexica people.

When the Spaniards arrived to the New World, however, they had a very different impression of these tiny birds found only in the Americas. Upon returning home, Europeans described them as delicate flying jewels—not fierce, mighty creatures like the Mexica people saw them.

So, how can a small bird have such a different meaning to two groups of people?

Dr. Iris Montero, a Visiting Assistant Professor of Hispanic Studies from Brown University, explored this juxtaposition in her recent SESYNC seminar titled “Pliny in Tlatelolco: Natural History between Two Worlds.” During her presentation, Montero explained what these contrasting views may indicate about different cultures’ interpretations of our human connection to nature.

Central to her talk was a 16th century text called Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España or General History of the New Things of New Spain. Written between 1575–1579, this bilingual text (Spanish and Nahuatl) is considered an early encyclopedia, meant to document the findings of New Spain; it was modeled after Pliny’s Naturalis Historia, written during Roman times.

This “Mexican encyclopedia” came a half century after the Spaniards arrived in central Mexico. In fact, 2019 marks 500 years since the conquistador Hernán Cortés arrived in Mexico—an event that would impact every aspect of the lives of Mexico’s indigenous peoples, including their spiritual relationship to nature.

The encyclopedia contained 12 books, with the longest, book 11, called “Earthly Things.” The Spaniards’ intention was to use this volume to promote Christianity’s prescribed hierarchy of nature, known as the scala naturae, or Great Chain of Being. Concerned about the indigenous people’s deification of objects in nature, the Spaniards wanted “Earthly Things” to differentiate the Christian God’s and humans’ places above plants and animals.

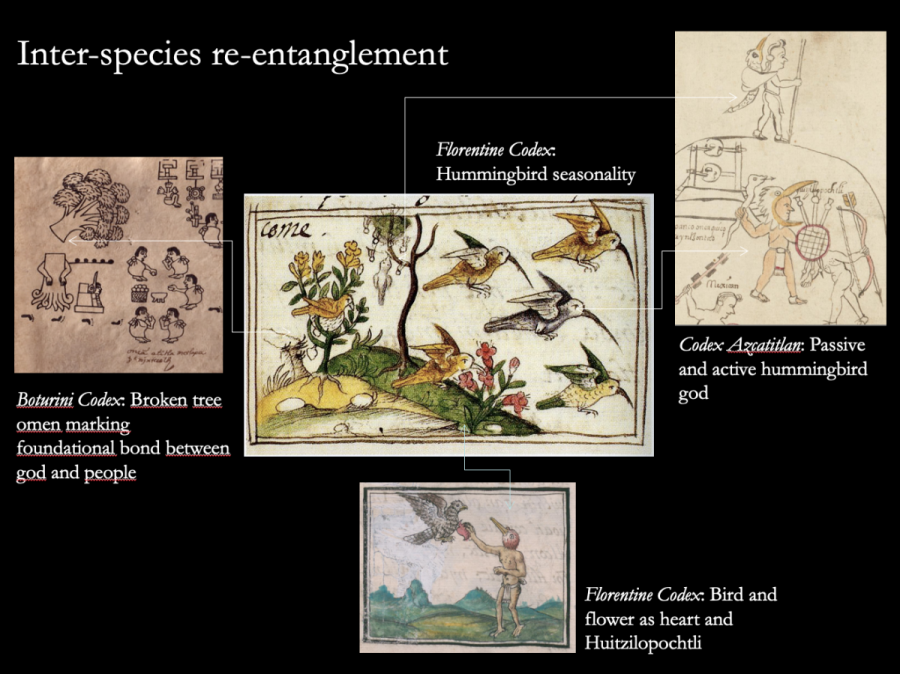

While book 11’s Spanish text contains observational descriptions of the birds that imply their place among the scala naturae, Montero explained that it’s the text’s Nahuatl wording and hummingbird illustration that show the birds may have a deeper meaning. Through her research, she found that indigenous peoples incorporated into this illustration symbolic references to foundational stories and artwork involving Huitzilopochtli. These symbols may indicate that in the context of producing book 11, the Mexica developed a very different approach to what “natural history” could express—a vision of nature as a part of themselves and their history. Montero also drew upon the scholarship of Ralph Bauer and Marcy Norton to discuss the concept of “entanglement” and the possibility of the re-entanglement of the indigenous people’s understanding of their connection to nature within the realm of natural history.

In her chapter, “Indigenous Naturalists” in Worlds of Natural History, Montero summarizes the indigenous imprint on book 11 this way:

“This is, if we think about it, the ultimate natural history. Not only is it a history of nature in narrative form, as in the Plinian tradition; it is a history where nature, in the form of an animal, plays the main role in the history of a people, through the mouthpiece of a god created to represent them both.”

Learn more about this seminar.